The Story of Kate Barnard:

Member of the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps

The Woman’s Army Auxiliary Corps learn to drill, circa 1917.

Image courtesy of the National Army Museum www.nam.ac.uk

Kate Barnard’s life story is unusual. She was brought up in Radcliffe on Trent by her grandparents, emigrated to Canada in 1913 as a young woman and returned to the U.K. in 1917 to help with the war effort. She served in the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps in Yorkshire and was discharged in September 1919, following illness. After some delays in securing an assisted passage, she returned to Canada in May 1920 to begin a new life. Her story has been assembled from documents held at the National Archives and other official records.

Kate’s story has been hard to trace because of discrepancies in the recorded information. She is listed with three different forenames: Kate, used in records from her birth to 1913; Katherine, which she uses to sign documents between 1916 and 1920 and then her name becomes Kathleen in Canadian records from 1923. Her birth year is recorded as either 1893 or 1894. She does not seem to know herself when she was born: when she enters her date of birth on official forms it is on a different day and a year later than on her birth certificate. Similarly, her place of birth is variously recorded as Derby, Radcliffe on Trent or Nottingham. Her mother has also been hard to find as her forename changes in the records from Martha Jane when a child to Jane as a young married woman and then Jennie when Kate is writing about her. The name reverts to Martha Jane on the 1939 Register and the England and Wales death registration index.

Kate’s birth certificate shows she was born on 27th April 1893 in Derby. Her full name is Kate Barnard and her parents were Richard Barnard, journeyman tailor and Martha Jane Barnard, formerly Gibson. Her mother registered the birth on 7th June, 1893; she was living at 1 Spa Lane, Derby at the time. These facts about Kate’s birth have provided a consistent thread in the construction of her story.

Before the First World War

The Green, Radcliffe on Trent

Kate Barnard’s father, Richard, was born in 1869 and came from Radcliffe on Trent. He was the son of John and Elizabeth (Bessy) Barnard and was brought up in a five room cottage on The Green. John was an agricultural labourer, born about 1827 and Bessy, who was working as a grocer in 1891, was born about 1832. Richard is known to have had four sisters: Mary born 1855, Catherine born 1859, Ellen born 19.12.1861, died 1946, Clara born 1865, died 1885 and three brothers, John Henry born 13.11.1867, William born 1872 and Charles born 21.1.1874. The 1911 census records John and Bessy as having ten children, two of whom had died by that date.

Richard married twenty year old Jane Gibson from Derby in 1891, March quarter. The census records them living at 2 Bunny Terrace, The Meadows, Nottingham. He was working as a tailor. On 6th January 1892, Alfred Barnard, son of Richard and Jane, was born in Radcliffe on Trent. His grandmother Elizabeth Barnard was present at the birth. Kate was born the following year on 27th April 1893 in Derby, where her mother was now living.

In 1901 Kate Barnard, age seven, was living with her grandparents John, age 73, and Elizabeth, age 70, at The Green. John was still working as a labourer. John’s son Charles, age 27 and a bricklayer’s labourer, was also a member of the household. Charles is recorded as Kate’s father on the census transcription but not on the census itself. This presumed relationship is a clerical error. Kate’s mother, recorded in the 1901 census as Jane Stokes, was now living in Nottingham with her son Alfred and Lewis Stokes, a coal miner. Her occupation is described as ‘curtain tape lace’. It has not been possible to trace Richard Barnard – he is not recorded in the 1901 census, on the death register, in passenger lists of people travelling abroad or in military records. Many years later, Kate’s uncle, John Henry, explained Kate’s separation from her mother in a reference he wrote in 1918 in support of her army application:

I have known applicant since her birth. She is my brother’s daughter. I am only qualified to speak of applicant as a relation who has had opportunities of observing her conduct generally and, having regard to her surroundings during childhood, I consider she has done great credit to herself. At an early age she was, through family circumstances, placed in the care of my mother (Elizabeth Barnard), where she remained until my mother died in 1912. She then went to Canada and returned to England about two years ago.

The 1911 census shows Kate had moved away from Radcliffe on Trent before her grandmother died and was living at 55 Turney Street, Nottingham, the home of her maternal aunt, Mary Ellen Hill (née Gibson) and her husband Walter Hill, a railway clerk. Kate’s occupation has not been recorded on the census. The household also included Mary and Walter’s four sons, Arthur, 17, William, 14, Eric, 11 and Everitt, 5. Kate’s maternal grandmother, Georgina Gibson, was a visitor. The house, a narrow, three storey terrace with five rooms, was on the south-east side of Nottingham near the River Trent in the area known as The Meadows.

There is no trace of Richard Barnard in the 1911 Census. Kate’s brother Alfred Barnard, age nineteen, was now living at 100 Brookend, Fazeley, Staffordshire. He worked in a colliery driving horses underground. The household also comprised Lewis Stokes, still working as a coal miner, his common law wife, Jane Stokes (Alfred and Kate’s mother) and their daughter Rose Ellen, age six, born in Nottingham in 1904. The house had four rooms. Jane is recorded as having had five children, two of whom had died. According to the census, the couple had been married for twelve years but the England and Wales Marriage Register shows they did not marry until 1922.

Emigration to Canada, 1913

During the early 1900s there was a sharp rise in emigration from Britain to Canada. Over a million people arrived from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales between 1902 and 1914. The numbers peaked in 1912 and 1913 when there were more than 300,000 arrivals. Immigration was encouraged by the Canadian authorities; its popularity among the British was linked to the possibilities the country offered for new opportunities. One of those seeking a better life was Kate Barnard.

In 1913, Kate, age nineteen, sailed from Liverpool to Canada on the S/S Dominion, arriving in Halifax on 25th January. She was with her friend Alma Barton who came from Sheffield. Kate’s occupation, like Alma’s, is recorded on the passenger list as a training hand, hosiery trade. The women intended to follow the same trade in Canada; it is possible that Kate and Alma met while working in a hosiery factory. Kate’s home address on the passenger list is ‘Uncle W. Hill’, 55 Turney Street, Nottingham and her religion is Wesleyan.

What happened to Kate in Canada over the next four years is currently unknown. Her friend Alma, age 21, was married in July 1913 to George Deaves McNallie in Brant, Ontario. He was a forty-five year old labourer originally from Essex and had been living in Canada since 1891. George and Alma were members of the Salvation Army. In 1918 the couple moved from Canada to Buffalo, New York, USA.

Applying for the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps

WAAC personnel line up for their pay, c.1917

Image courtesy of the National Army Museum www.nam.ac.uk

The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps was formed in January 1917, in part to offset the huge losses of manpower at the Battle of the Somme. The initial idea was for women to serve as clerks, telephonists, store-keepers, driver-mechanics, cleaners, cooks and waitresses to release more men for the front line. These mundane and mainly domestic jobs helped to keep the army going. For the minority who went abroad, the tasks expanded to include working as printers, bakers and cemetery gardeners. The women were obliged to keep fit and their exercise regime included playing hockey. A different language and command structure was used for female members of the Army. Women enrolled rather than enlisted, Officers were called ‘Officials’, NCOs were ‘Forewomen’ and Other Ranks were ‘Workers’. The organisation and discipline was similar to that of the factory floor. Many of the thousands who enrolled were young working class women attracted by the offer of free accommodation, meals and clothes. Whereas the Red Cross was able to recruit women whose family finances were sufficient for them to work as volunteers, the W.A.A.C. appealed to those who needed both a wage and accommodation or a change from exhausting work in munitions factories. The army was an attractive option for Kate Barnard, who had been shunted between different families in childhood and did not have a permanent home. By 1918 nearly 40,000 women had enrolled in the WAAC. Around 7000 served on the Western Front and the rest remained in the United Kingdom.

Forewoman in her office in France.

Image by Lt. Ernest Brooks, courtesy of the National Library of Scotland

In July 1916 Kate, now calling herself Katherine, applied for entry to the U.K. from Canada. She sailed from Toronto to Liverpool on the S/S Grampian, arriving on July 17th under the name of Kitty Barnard ‘with a view to offering my services for national work in connection with the war’. A few months later, Katherine began her army life in March 1917 as a civilian waitress at Scotton Camp, Catterick, North Yorkshire, home of the Royal Field Artillery. She applied to join the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in March 1918; like all women she had to enrol through an Employment Exchange. Her application was processed by the Exchange in Northallerton, North Yorks.

There are a number of letters, held at the National Archives, from the War Office concerning her application together with copies of references. On the 5th May 1918, the canteen manager, Lilian Orton, wrote to the War Office saying Miss K. Barnard, 189 Canteen, ‘A’ Battery, 5th Res. R.F.A., Scotton Camp, Catterick, Yorks has my permission to volunteer for service in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps and I am prepared to release her from my employ in the event of her being accepted for service in the Corps.

A letter from the Employment Exchange in Northallerton to the Divisional Office of the Army in Doncaster, dated June 6th 1918 states: I beg again forward for consideration application in respect of undermentioned applicant, who has now obtained her employer’s consent.

Three references were written to support her application. The first was from Charles Stokes, an insurance agent living at 37 Coleshill Street, Fazely, the same street in which his younger brother Lewis lived. He wrote that he had known the applicant for two years as a personal friend of the family. I know nothing of applicant’s qualities catering as Forewoman waitress but am of the opinion that she would soon become adapted to the work. The canteen manager, Lilian Orton wrote that she had worked for seven months as a coffee bar charge hand: she is a thoroughly capable waitress and in every way suitable for the position. Her work has always been satisfactory a) absolutely reliable and steady b) industrious c) perfectly honest (the reference is undated). Katherine’s uncle, police sergeant John Henry Barnard, whose reference of 5th July 1918 was cited earlier in relation to Kate’s childhood, added my impression was that she had grown into a well informed and respectable young woman. If it is of any assistance to you in forming my opinion of the value of my Kate I may say I have a 30 years character … (illegible word) and have brought up a respectable family.

Katherine was finally accepted in the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps on July 23rd 1918 at Doncaster, over a year after she had begun her application. Her service number was 41674 and military unit was 2 WAAC. Her British Empire Certificate of Identity includes the following information:

Name: Barnard, Katherine (Miss)

Date of birth: 7th April, 1894

Age 24 and 3 months (her birth certificate shows she was born 27th April 1893; she has described herself as a year younger than her actual age)

Occupation: Waitress

Permanent Address: 10 Midland Cottages, Rectory Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham

Physical description: height 5ft 4ins, hair brown, eyes brown, medium build, weight 127 lbs

Next of kin: mother Mrs Jennie Barnard, 14 Coleshill Street, Fazeley, Near Tamworth, Staffs.

The army provided a uniform for its members; it included outer garments but not underwear. Katherine signed for the following items: 1 hat badge, 1 felt hat, 1 coat, 1 greatcoat, 1 gaiters, 1 frock, 3 collars, 4 overalls, 2 pairs of stockings, 2 sets of shoulder titles, 1 Brassards (arm bands).

Serving with Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps

Officers’ canteen, Le Havre, with a member of the QMAAC behind the bar.

Image courtesy of www.histomil.com

In April 1918 the WAAC was renamed the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps when Queen Mary became the army’s patron in honour of the bravery of female personnel in France at the time of the German Spring Offensive. Katherine Barnard therefore became a member of the QMAAC rather than the WAAC. Details of her service are slight. She was initially based in York at the depot of the West Yorkshire Regiment where she served for about ten months. She was given sick leave from April 4th 1919 to May 6th. Following a transfer to Emergency Quarters, Scarborough on May 2nd, she was given sick leave again from May 7th to June 14th. She was transferred to Catterick to the Lines Cadres on July 5th and then moved back to Scarborough on August 11th 1919. It is clear that she was unhappy with her role in the army and tried to leave in June 1919. An official letter written to the War Office on June 26th 1919 states the above member is attached to the Emergency Quarters, Scarborough. She is anxious to change her category to Orderly, Storekeeper or Clerk and unwilling to continue work in her present category. The unit administrator, however, states that she does not consider her suitable for this change. As Barnard openly (hole in record, words missing) put on draft that she intended to absent herself (words missing) if posted as a waitress, I shall be glad if authority may be given to discharge her on grounds of termination of engagement. The request for termination of employment was turned down by the General Officer, Commanding-in-Chief, Northern Command, York who stated If she refuses to go on duty and absents herself she should then be treated as an absentee and dealt with accordingly. The discharge is not approved by this Department. There was a change of heart in August 1919 when she was discharged on compassionate grounds due to ‘septic arm caused by abscesses’. She was eventually discharged from Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps at Scarborough on September 11th 1919 after taking 28 days furlough.

Return to Canada, 1920

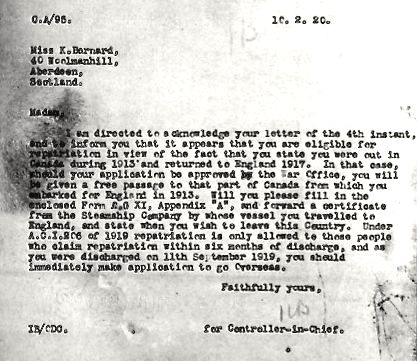

Katherine’s military service amounted to working for ten months at the West Yorkshire Regimental barracks and four months stationed at Emergency Quarters, Scarborough. Before joining the army she had worked as a civilian for sixteen months in the canteen at the Royal Field Artillery barracks, Catterick. After she was discharged, she moved to Aberdeen for unknown reasons. There is a set of letters in the National Archives between Katherine and the War Office regarding her repatriation to Canada. It begins with her request to leave the U.K. under an army scheme that would pay her passage. On February 4th Katherine wrote:

Dear Sir or Madam,

I wish to gain particulars with reference to free passage for demobilised QMAAC members. I would like to state that I am anxious to proceed to Canada this coming spring. I would like to state also I was out there in 1913 and returned home in 1917 and went straight to war work until September 1919 when I was demobilised at Scarborough. I joined the QMAAC in July 1918. Prior to that I worked sixteen months in an army canteen. Hoping to receive a favourable reply in due time.

I remain yours faithfully,

Katherine Barnard.

Her letter disguises the fact that she did not ‘go straight to war work’: a few months elapsed between her arrival in July 1916 and working in the RFA barracks at Catterick. She received the following reply a week later giving her permission to apply for a free passage but was told that it was time limited:

Katherine replied on 16th February, no longer able to avoid the fact she had lied about the date she disembarked in England:

I herewith enclose my passage of July 1916 hoping this will furnish all necessary information as I have no other certified. Trusting this will prove satisfactory. I need to be able to leave for Canada by … everything … should be approved and clear by the authorities of the … . Thanking you for your kind information,

Yours faithfully,

Katherine Barnard.

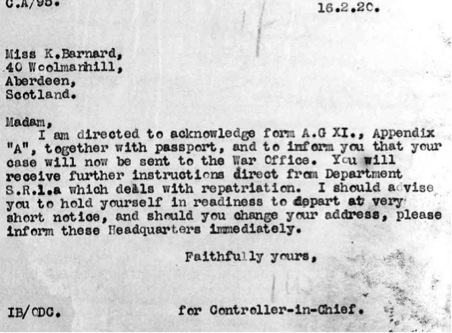

It appears that she was still entitled to a free passage. At this point, with her papers in order, procedures were put in place to expedite her journey:

Katherine’s letters show she was determined to secure the best possible outcome for her return to Canada by attempting to negotiate with the War Office. She replied straight away on February 18th requesting if she could travel second class if she paid the difference:

Sir,

With reference to your letter of 9th inst. and information of conditions of travel, I would like to enquire if I may travel second class on payment of difference to the shipping company, as I would prefer that for the sake of convenience. Would you kindly give information of amount due now and way of making the difference for travelling second class? Thanking you for your kind attention.

I remain, Sir, yours sincerely, K. Barnard.

By March 1920, Katherine had moved to 77 Bon Accord Street, Aberdeen and was having doubts about departing as soon as possible. In the following letter, in which she continues her attempt to negotiate with the War Office, she tries to delay her passage. She explains that she has been suffering from abscesses, was receiving good treatment and wanted to remain in the U.K. until she was better:

Dear Sir,

With reference to my application for repatriation to Canada, I would like to state that I would like if possible to cancel my application. Unless I could make the journey towards the end of the summer. Would that be possible? I have suffered with sixteen successive abscesses during and since leaving the Army and would like to stay here where I have received good treatment for septic system as the north air is doing me good. Will that hold good later on please. Thanking you in anticipation of favourable reply. I remain

Yours faithfully,

Katherine Barnard

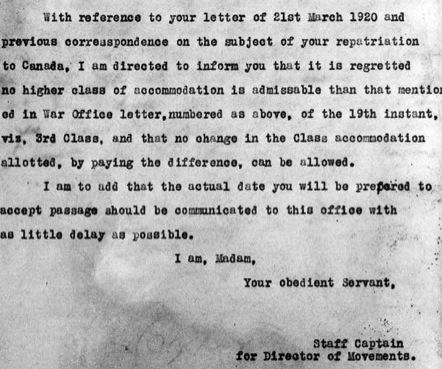

The War Office, however, was not prepared to wait. Katherine was told she had to leave by March 1920 or she would forfeit her right to a free passage. However, a deferment might be possible if she could provide a medical certificate. A further letter was sent regarding her request to travel second class:

Katherine, realising she was in danger of forfeiting her passage, replied by stating that her septic arm was ‘considerably better’ and agreeing that it was best for her to go as soon as possible. A passage was arranged for her on Friday 30th April on the Melita with free transport from her home in Scotland to embarkation in Liverpool and then free transport from her port of disembarkation in Canada to her destination. However, this passage was cancelled by the War Office without explanation. A new journey with the same provisions was immediately arranged on the Grampian, leaving Tilbury Docks on Tuesday 4th May, 1920. The passenger list shows Katherine embarked; it describes her as a ‘returned Canadian’ who had previously lived in Toronto. Her date of birth and age is not noted; she has no occupation listed. She disembarked in Montreal, Quebec on 15th May.

Marriage in Canada and family matters

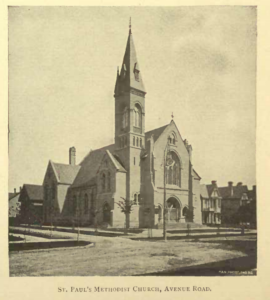

St Paul’s Methodist Church, Toronto in 1891.

Source: Adam, G. Mercer: Toronto, old and new (1891).

Kate’s life appears to have improved after she returned to Canada. She settled in Toronto and began working as a nurse. At some point she met the man who was to become her husband. Kate/Katherine, now calling herself Kathleen, married Arthur Edward Brown at St Paul’s Methodist Church, Toronto on 17th March, 1923 in the county of York, Ontario. Her father’s name on the marriage certificate is Richard Barnard and her mother’s is Jennie Gibson. Kate/Kathleen’s occupation is given as ‘nurse’ and her address is 54 Dupont Street, Toronto. The certificate states she was born in England and her age was twenty eight; according to her birth certificate, she would have been twenty nine years old. Arthur Brown was a billiard marker, that is, a man who keeps the score and looks after the players in billiard matches. He was living at 105 Bernard Avenue, Toronto with his parents and brother at the time of the marriage and was thirty five years old. Arthur was born in Aylestone, Leicester, son of John Thomas Brown and Clara Richardson and emigrated to Canada in 1909 to seek employment as a marker. His parents and younger brother Harold followed on in 1912; his sisters Ida And Dorothy travelled separately the same year to join them. Before then the Leicester based family had been working mainly in the boot industry.

Although it has not yet been possible to follow Kate’s story after her marriage, there is some further information available about members of the Barnard family. Kate’s grandfather, John Barnard, died in 1917. Her mother married Lewis Stokes in 1922. Her brother Alfred married Ethel Jenkins in 1921; his wife died in 1935. The 1939 Register shows he was a widower working as a coal miner and living in Coleshill Street, Fazely, next door to Lewis Stokes, his mother, now described as Martha Jane Stokes, and their married daughter Rose Ellen, together with her husband and their child. Lewis, now a retired miner, died in 1942. Martha J. Stokes died soon after in 1944. Alfred Barnard died at the age of fifty-nine in 1951.

Ellen White, maiden name Barnard.

Sister of Richard Barnard, aunt of Kate Barnard.

Photograph from Public Member Tree at www.ancestry.co.uk.

The Barnard family maintained a close connection with Radcliffe on Trent. Richard Barnard’s sister Ellen (Kate’s aunt) lived in the village all her life. She married William White and brought up a family. In 1939 she was living on Widows Row, close to The Green where she had lived as a child. She died in 1946. Richard’s younger brother Charles also stayed in Radcliffe. He was working as a builder’s labourer in 1939 and lived on Bailey Lane. John Henry Barnard, Kate’s uncle, who wrote her a reference when he was living in Harrow, stayed in the south of England. In 1939 he was a retired police sergeant living in Fleet, Hampshire.

Kate Barnard was an independent woman whose life was unconventional. Instead of staying in Nottingham and working in a factory, she chose to emigrate to another country as a single woman and then return to Britain to join the army. During her working life she progressed from factory hand to army worker and then became a nurse. Although her career in the army was disappointing in that she remained ‘stuck’ in the position of waitress, she was still able to use the opportunity to obtain a free passage between Canada and the U.K. and to live in different parts of the U.K., including Scotland. Having returned to England to serve her country, she made a clear decision to leave again in 1920 and go back to Canada. She would not have had an easy time in the army partly because public reaction to female personnel was mixed. On the one hand, it was recognised that the army needed to employ women but on the other hand newspapers undermined servicewomen by publishing rumours about their ‘immorality’. It is women like Kate who helped break the mould of traditional expectations and jobs for women and paved the way for their greater involvement in the forces during the Second World War and up to the present day.

Author: Rosemary Collins