A Personal Account of World War I

by G. V. Elwin

Chapter 3

From Martinsart to Passchendaele: 1917

After Christmas 1916 and our week of rest it was back to Martinsart again and the daily firing of our guns. Spells of duty at the observation post alternated with spells at the battery command post, always day and night was the infernal repairing of broken telephone lines. How we used to curse the Germans when we set out on a dark, wet night, ploughing through ankle deep mud, telephone line running through our hands until the broken end was reached.

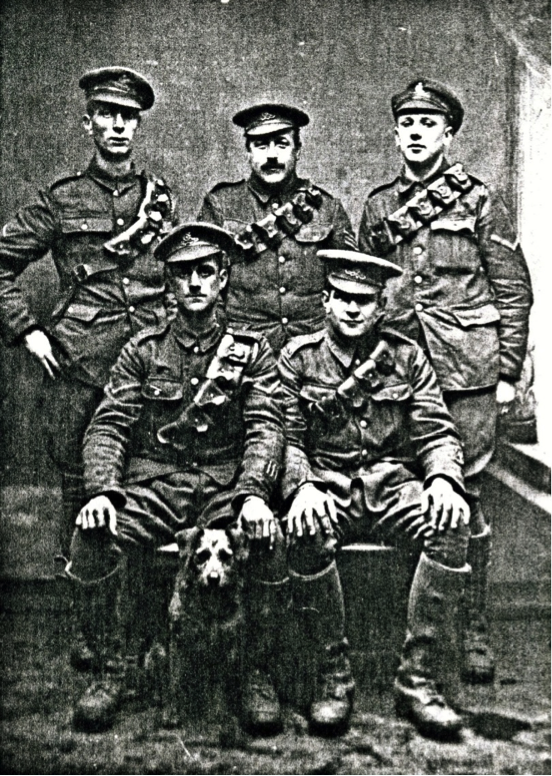

Gilbert Elwin and members of his battery

Back row l-r, Jock McPhee, Sergeant ‘Tubby’ Kent, Gil Elwin

Front row Jim Pankhurst, James Pearce and Mascot of 112th Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery

We created one simple enjoyment. We went ratting wherever we saw traces of them. We would go, three or four of us, when off-duty to a spot say 300-400 yards from the battery where signs of rats were visible. We had an empty five-gallon oil drum to hold the rats we killed, sticks of the explosive cordite and a dog!

We had acquired this stray dog some months earlier. It was lean and hungry and we fed it scraps of bread. It was an Airedale type of dog and remained with the battery until the end of the war. It gave us much amusement because every time a duty officer received a target to fire upon, the officer would call loudly “Action!” That one word was enough for our dog. Down would go his tail and he would race away and hide somewhere until the firing ceased. Then he would return jumping excitedly and so happy that it was all over for the time being. This happened many times every day.

Our method was to put sticks of cordite in a rat hole, one of us would stand with a shovel full of earth, the explosive was lit with a match at the end of the cordite sticking out of the hole. The earth was thrown at once on the lighted end when flame and smoke poured out of all the connecting rat holes. Many times we had as many as a dozen rats bolt out of different holes. We were ready with sticks and our dog would pick up several and kill them. We often killed twenty to thirty rats on an outing.

It was at Martinsart too where we had an 18-pounder battery of six guns just in front of us. It did a lot of shooting and obviously did a good deal of damage to the Germans. One day the Germans had had enough and they absolutely smashed up that battery position completely. The men left the battery position without casualties at the start, but all the guns and ammunition were destroyed and as a firing unit they ceased to exist. I went over afterwards to have a look and the disorder was terrible. No doubt they were withdrawn and had to build up again into a fighting unit.

We had a battery barber to cut our hair who had an extra one shilling per day for doing the job. I recollect going to him one day at Martinsart. He served on the guns as well as his barber job. He built himself a small ‘residence’ of sandbags some three feet high and about six feet by four feet inside, topped with old doors from the village. He was a redheaded lrishman with the name of McGinn. This place was situated in a dry dyke alongside the remnants of a hawthorn hedge. Incredibly, he had a small wood and very smoky fire inside to keep warm. When I crawled in on hands and knees, he was sitting on the ground smoking his pipe despite the heavy smoke from his fire. On my entry he said: “Keep low, you will be alright.” I sat on the earth floor and he cut my hair by the simple process of running his hair clippers all over my head so that it was almost shaven.

In addition we had a sanitary orderly who was also paid extra for this extra duty. I won’t give the men’s name for him as it was rather rude. His job was to prepare at every new position a toilet. He first dug a small trench about six feet long, two feet deep and one foot wide. Around it he fixed, on four six foot posts, a screen of canvas. Over the trench and along it he fixed up a six foot long pole on supports at both ends. This was our toilet and it was quite common for two to three men on the pole at any one time. He dusted the trench bottom daily with chloride of lime.

It is interesting to note here that on our right front was Mesnil Church standing in some war torn trees. It was on top of the high ground on which we had our observation post. I never went to it but is must have been badly damaged.

Further to our right was the clearly visible Albert church. Albert was a fairly large empty township repeatedly shelled by the Germans as of course our troops were in occupation. We could clearly see the large golden figure of Madonna hanging head down from the spire on top of the church. Although stonework of the spire had been shot away and the figure was hanging by steel rods only, the Germans never succeeded in bringing it down completely. There it hung for all to see until the end of the war. A symbol I wonder? I don’t know.

St. Leger: April – August 1917

We stayed at Martinsart for three to four months in action i.e, firing our guns every day and night. It was about April 1917 when suddenly the Germans withdrew from their positions and on our sector of the front. They fell back several miles to newly created and much stronger positions. The withdrawal was so sudden and complete that we were stopped in the middle of a shoot as the enemy was beyond our reach and our follow up infantry might be in the area we were firing upon. Strangely, this left us with one gun with a shell in the barrel. After ramming home a shell in a gun barrel it is impossible to take it out again and must be fired. The cordite cartridge can be removed but not the shell which has been rammed home until its copper driving band around the base of a shell bites into the rifling in the gun barrel.

At once it was up and away for us to follow up our advancing infantry. On our way forward we fired our one shell left in the one gun into a hillside. I can’t remember how far we travelled but it was many miles. Of course the Germans had blown huge craters with mines in all the roads which our guns needed. During this movement, we had no shelter from the everlasting rain, sleeping in the open just when and where we could, dressed as we were in our overcoat, steel helmet and gas mask. So we slept where we were stopped, in the open, in the rain. I wonder how many people have slept as I did, laid out flat on a waterproof ground sheet, gas mask as a pillow, helmet on the upper-sides of one’s head and raining pitilessly many times. Frequently we awakened shivering with cold, but the modern world’s head cold was unknown.

Our destination turned out to be St. Leger, a small village at the end of a valley.

St. Leger village by official war photographer Lieutenant John Warwick Brooke.

Photograph from the papers of Field Marshal (Earl) Haig (1861-1928), courtesy of the National Library of Scotland

The road on which we were travelling was on top of one side of the valley and the Germans had blown a huge crater completely destroying the road. A German soldier lay spread-eagled face down at the bottom of the crater, but that did not bother us. It was no business of ours. Our job was to get our guns round this crater and down into the valley out of sight of the Germans. This involved taking the gun through deep mud on each side of the road. All night everybody struggled. We fetched wooden doors and all helpful material from St. Leger to put under the gun wheels. It was dreadful. The mud was calf-high; dawn was approaching and we still had one gun to get around the rim of the crater. If it were still there at daybreak we would have been in full view of the Germans and they would have concentrated their gun fire on us. Mercifully, as dawn broke a heavy mist came down and allowed us to clear the last gun down into the valley. It sounds simple writing about it now, but the memory of the spinning gun wheels in the mud, without the gun moving one inch is still with me.

We established our guns at the head of the valley, but our signallers’ immediate task was to establish an observation post with a telephone line connected. The land sloped downhill to Croiselles which the Germans occupied. On the steep decline we fixed up our O.P. so that it was only possible to occupy or vacate it in darkness. It was a precarious position and only lasted about a week. The whole of the slope was covered in corn stubble and one of the stooks of corn served as our O.P. We had to crouch all day and hardly dare move until darkness came down. To make matters worse, the ground around us was littered with dead English soldiers of either the North or South Staffordshire Regiment. They had advanced in extended order and had been mowed down by enemy gun fire. I can still picture them in my mind, the grotesque shapes and attitudes as they fell, some with blood having run from their mouths. It all sounds brutal and callous now, but it was there and I saw it all for that one week.

As it affected the morale of the living soldiers, it was not army policy to leave dead lying around so during one night all of the bodies were removed. We too moved our O.P. to the other side of the valley on the rim of the high ground. It was much better there as we had a fifteen foot dug-out for our telephone and a good look-out position. The enemy shelled us from time to time. On one occasion they blew up our latrine (army word for toilet) much to the disgust of our sanitary orderly who had to prepare another one.

Our only other casualty was a Canadian who was with us called McKnight. He insisted safety was in being alone so he used to hollow out a six or seven feet long hole and one foot deep in which he lay and slept. One night the Germans started shelling us again and they put one shell right under him blowing him sky-high killing him instantly.

Dangerous encounters at St Leger: 1917

Another serious incident occurred at St. Leger. Some bright officer at headquarters had the idea, which he put into effect, of one battery only doing all the shooting so that the enemy would not know the various positions of the other batteries. Our battery was chosen to do all the shooting. What a crazy idea it was. It was our duty to shoot at enemy activity on the roads, in the trenches and wherever enemy movement had been observed.

So many targets came through to us that we were many hours behind in actually shooting at them. Our gun crews became exhausted but still it went on. Then it happened. The guns became so hot, despite being continuously draped with cold, wet sacks, that one exploded. A shell had been rammed home, a cloth-covered cartridge put into the breech, but before the man could close the breech the cartridge ignited and blew back instead of exploding and driving the shell from the barrel. All the gun crew were wounded, some badly, and the man whose job it was to close the breech and actually fire the gun was killed instantly. His body was found 15-20 yards away. He had been decapitated, his head being yards from his body. His name was Tom Mundy, a regular soldier. Needless to say this stupid order was then cancelled.

I have omitted to record that at the commencement of our advance from Martinsart when we were on territory occupied by the Germans, I was one day taken by our Sergeant on a trip forward to find suitable places to run our telephone lines. He was a loveable, easy-going man, never unkind, always willing to take part in difficult situations as they arose. He was short and fat with the name of Kent, known to everybody as ‘Tubby Kent’. His home was at Eastbourne. We went along the side of a very narrow cleft of land known as Y Ravine. Halfway along on our left Tubby suddenly said: “Look at that Peter. Come on”. I looked left and in a shallow shell hole, curled around was the skeleton of an English soldier. Obviously he had been wounded months earlier and crawled into the shell hole to die a miserable death. All his flesh had been eaten by rats but the skeleton still retained some of his uniform. I took one look and hurried past after my sergeant. Let me explain now I was called Peter by everyone. I don’t know the reason. I don’t know how it originated but it remained my name all the time I was with the battery.

Another incident was on the way to St. Leger when we spent one night in a German dug-out. It was the usual well-built affair at least twenty feet deep. Halfway down were ends of wires sticking out the mud walls and hanging down about one yard. We were seasoned soldiers but were reminded by our sergeant not to touch the wires as they could be connected to some booby trap to blow in the dug-out. The Germans were clever in creating booby traps whenever they retreated and we were always conscious of the need to look out for them.

Going up to and coming down from our O.P. we had to go along a short trench occupied by two infantrymen. I have no idea what they were there for but each time we passed them, up or down, they gave us a mug of tea which was gratefully accepted. This went on for some weeks, then we came down one morning we found them both dead stretched out side by side in their short trench. It was a shock pulling aside their hanging piece of canvas and seeing not mugs of tea, but two pairs of nailed boots facing us. No one else was there and next day they had been removed.

Going up to this O.P., we climbed rising ground and were able to look down into what had been St. Leger market place. It had been a covered market but now German shelling had destroyed the roof which had fallen down in pieces. That was nothing strange to us, but the horrible part was that some unit had used the covered market as a place to shelter horses. When the shelling started it was obvious the roof collapsed on to the horses and about twenty lay dead amongst the ruins of the roof and walls. I can still picture them lying there amongst brick and iron rubble, their bodies blown up like balloons with the internal gases in their stomachs – a never to be forgotten image.

We signallers had established ourselves in a dried-up dyke at the side of the valley. It was about five feet deep and we lay on our groundsheets at the bottom. It was very comfortable and as always we increased the comfort in little ways as time went by. A waterproof roof was fixed up, flat pieces of ground created to sleep on and candles to light up the interior. When not on duty we spent a lot of time in this hideout. Until a period of heavy rain started when all at once a rush of water came pouring down and we were completely swamped out. Everybody made a hurried exit, grabbing up blanket, groundsheet and personal belongings. It was night time, of course, and raining.

We never went back to our dyke. We moved across the valley into cave-like excavations in the hillsides. It was at this point that I met a man from my home village of Radcliffe on Trent. His name was Bob Wheatley and was the son of the local joiner. He was going, with others, to the trenches to take part in a night bombing raid on the German trenches, a very dangerous operation. He carried a haversack filled with Mills bombs, the haversack stuffed with hay to prevent rattle. Mills bombs were deadly hand held bombs of steel, inert until the pin blew out when thrown. I never saw him again in France but he survived the war and afterwards I met him in our village.

Third Battle of Ypres: July 31st – November 10th 1917

We looked down from the O.P. on the village, a large one, of Croisselles, shelling all German movements. Time was passing. It was August 1917. I was on duty at the O.P. one night taking down targets for our guns to fire upon. It was about 4 a.m. when suddenly the transfer of targets was suspended and the following message came through to me. “To O.C. (Officer Commanding) 112 (our battery number) three acks” (meaning full stop in signals language). Then the message started as follows: “Bombardier G. V. Elwin will proceed to England on leave on 13th August to 23rd August. He will report to the R.T.O. at Achiet-le-Grand at 2 a.m. to take up his papers.” There the message ended. I was astounded and delighted of course. To take down the message myself seemed somewhat uncanny. The sender of the message at headquarters cut in to say “lucky blighter.” I replied “It’s me.” What a strange coincidence.

I left our battery about 6 p.m. on the 12th August and waltzed several miles into the back areas until I reached the rail-head at Achiet-le-Grand. I was checked off on a list, issued with several documents such as railway ticket which took me all the way to Radcliffe on Trent and back again to Achiet-le-Grand. A certificate was also given to me saying I was free of vermin and scabies. The certificate was just routine because I was not examined by anyone and I certainly was not free of vermin. I had body lice in the seams of all my garments. Body lice are tiny crab-shaped insects about as large as a pin head, colourless. They did not bite, just crawled on the skin. They did however, lay clusters of eggs and it was very necessary from time to time to go along the seams of our garments with a lighted match to burn out both lice and eggs. On the two occasions I went home on leave from France I would go straight to my father’s greenhouse, strip off all the clothes and leave them in the greenhouse, wrap a towel round me and then straight to a hot bath. Then I put on civilian clothes and over the next day or two gradually de-liced and washed all my garments. Within a few days of being back in France I was lousy again.

I spent a wonderful eight days at home becoming engaged to the girl who was later to become my wife and the mother of my three charming and wonderful daughters. I had written to her every week all the time I had been in France and she had written to me in the same way. I wrote all of mine when I was on duty in the middle of the night, that is, during quiet periods.

Boesinghe: August 1917 – October 1917

I arrived back at St. Leger to find the battery had moved in my absence. The gun positions were empty and the many little sleeping places empty. So exactly as my former leave, I had to find the battery. I made several enquires at different headquarters and at last found they had gone to a place called ‘Boesinghe’ some fifteen to twenty miles (I think) away.

I walked and found them but what a difference to St. Leger. We were outside the village (ruined) and everybody except the officers had made themselves little sandbagged sleeping places on the ground. I wandered around trying to find a sleeping place. My friend Jim Pearce had gone in with another friend of his and he had no room for me. From then on I drifted away from him and found a friend in a man called Norman Newton. He had come to the battery with the two extra guns and was junior to me in experience. We became firm friends which went on long after the war ended and we were both back again in civilian clothes. His home was Stoke-on-Trent and he came to Nottingham to my wedding after the war ended.

I found Norman Newton lying inside a sandbagged structure he had built for himself. It was about seven feet long, five feet wide and three feet high. It was hard earth and entrance was on hands and knees when you twisted sideways and sat up with your head almost touching the roof. I looked inside, told him I wanted somewhere to sleep and he said at once: “You can come in here if you like.” I gratefully moved in, laid out my groundsheet and blanket alongside his and went to sleep. It was a strange place to sleep in but we both used it all the time we were at Boesinge. I found him a grand fellow, always cheerful, and we did many duties together.

To get to our O.P. at Boesinge involved a strange route. First we had to cross a canal normally about fifteen feet wide and full of water, but now so badly shelled the water had drained away and only about two feet remained at the bottom. A duckboard track floated originally on empty, but water-tight, oil drums had carried the track but the drums had been perforated by shellfire and consequently the track was below the water level. So we had to walk through about eight inches of water across the bottom of the canal. Once across everywhere was sheer desolation, the ground pock-marked with thousands of shell bursts, no trenches and in full view of the Germans. Consequently only movements by night were possible. We had run out two telephone lines between battery and O.P. along different routes to avoid as much as possible turning out during daylight in full view of the enemy.

Our O.P. was on ground level as it was impossible to dig down because of the waterlogged ground. It was situated in what once had been a copse of small trees with about four inch trunks. Now they were stripped of all greenery and were just eight to twelve feet stumps. On ground level the broken-off branches lay like dead undergrowth to a height of some eight feet. Excellent cover for us provided we went to and fro in darkness.

We built a sandbagged wall about five feet high on which we stood our telephone, binoculars, telescope, etc. about eight feet long. We also erected a sleeping place against another similar sandbagged wall, laid an old door on two empty cartridge boxes and used this for sleeping when off duty. All materials had to be carried up in darkness. I must record that I never slept in this sleeping place for the simple reason that it was alive with mosquitoes which filled the air with a loud humming noise all night long. I just stood up all night leaning against the wall on which the telephone stood. I was on duty one night with a fellow called Dickie Dormer and he said he was going to sleep on the wooden door inside the sleeping place. Next morning he emerged with a face terribly swollen by mosquito bites. He could hardly talk because of swollen lips and he could hardly see as his eyes were also so very swollen.

At Boesinge our officers lived in a large oval topped corrugated iron hut half sunk in the ground. It was very comfortable but it was also rat-ridden. They knew how we dealt with rats by the use of cordite but it was never talked about because it was a serious matter to break open gun cartridges. After a time, however, they sank their pride and asked us if we would do anything about their rat problem. They knew very well what we would do. We asked to have the hut completely empty of human life for a period of one hour. This was arranged and we carried out a complete de-ratting operation by the use of cordite. We killed between twenty to thirty rats and life was much better for the officers as a consequence. It was very rarely that other rats came back into the rat runs as the cordite smell was strong in their runs for a long time afterwards.

Passchendaele: October 1917

We lingered miserably for some months at Boesinghe, in action doing the usual firing of the guns. It was about October-November 1917 when we moved to a hellhole that was called Passchendaele. To give a general impression of the area let me just write that if you looked front and back, to the left and to the right, there was an unbroken vista of nothing but thousands upon thousands of water filled shell holes. The ground had been turned over time after time and nothing, trees or buildings, was visible. It was complete and utter devastation.

I must deviate here to describe army duckboards. There were two varieties. The one usually used to lay along trench bottoms was six feet long and consisted of two bearer pieces of hardwood six feet long by three inches by two inches. Across these bearers were nailed about a dozen or so of thick oak strips with gaps between the strips. They were very heavy especially when sodden with water. The smaller variety was much lighter in weight being only four feet six inches long and made of softwood. It was not used so much in the trenches.

We had brought up two guns with very great difficulty and placed them in firing positions just below the top of a slight rise in the ground. I well remember that night, one of the worst ever experienced in France. Floundering in mud everywhere. Horses straining to move the gun a few feet at a time, slipping down, getting them up again and all the time raining continuously. All night long we laboured and all next day also. We were ready to drop down in the mud we were so tired. In fact that is what we did. It was still raining and I was wandering about looking for somewhere to sleep when I came across two of my close pals, Jim Pankhurst and Jock McPhee lying side by side in a slight depression in the ground. They said there was room for me so I gratefully laid out my groundsheet, gas mask as a pillow and slept. And all the time it rained and was dark. Next morning we arose shivering and wet but we had a job to do of our own. We had to run out two telephone lines to a forward O.P.

Now let me describe the Passchendaele battleground as we found it. As I have previously written as far as the eye could see, front, rear, left and right was an unbroken vista of thousands of shell holes. Every one of them full or half-filled with water and many of them yellow with mustard gas. To walk over them was an impossibility so two tracks had been laid leading forward. One was named Hunter Street and the other Clarges Street, both names of London streets. We mainly used Hunter Street but of course it was not a street at all. It was just a twelve inch wide duckboard track which wound round the rims of shell holes in tortuous fashion, at times almost coming back on itself. When meeting, say fifty men coming down, it was necessary to put one foot in the mud at the side of the duckboard and keep one foot on the duckboard.

Any time, day or night, the Germans shelled and destroyed sections of the track and in a similar manner our Royal Engineers repaired it. It was the only way – except for Clarges Street – to get to the front line positions.

Clarges Street was a much different type of approach to the front line and the infantry positions. It was designed for wheel traffic and was some eight feet wide. First of all fascines of brushwood were laid on the mud. On top of the fascines were placed railway sleepers joined together by heavy steel staples. It gave a good firm track, slightly wavy, but solid to walk upon. Every night supplies of food, water, ammunition and exchange of troops went up and down this track. Day and night at odd intervals the Germans shelled Clarges Street. I visited it only once out of sheer curiosity, also because it was a highly dangerous place to visit.

It was a staggering sight. Every night wheeled food kitchens, wheeled water carts went up to the infantry. Ammunition went up on the backs of mules, each mule led by one man. Eighteen pounder shells were carried in special slings of four on each side of the mule’s back. Imagine all this traffic on Clarges Street, going up and coming down in the darkness and then German shelling starts up. Immediately all is confusion, no-one can go either up or down. Men are killed, mules killed or maimed. My visit to Clarges Street was in daylight and I looked up and down the track and saw on both sides, off the track and in the mud, dozens of food kitchens, water carts etc., damaged and pushed off the track to be out of the way. Worse still there were scores of dead mules lying both sides of the track, their stomachs blown up like balloons with gases formed in their dead bodies. Of course there were no dead soldiers, they were taken away immediately. It was bad for the morale of the living soldier to see dead comrades. Such was Clarges Street, a triumph over the mud, but a day and night hell for the unfortunate men and mules who had to traverse it. I shall never forget my sight of it. The two so called streets went forward over the shell pocked ground at a distance of about half a mile

The Germans had defended this area by the building of concrete pillboxes and concrete blockhouses. These were littered all over the place. There must have been hundreds of them, but now three-quarters full of water and uninhabitable

Such was the area over which we had to run our two telephone lines to our O.P. It was easily done. We simply unwound the cable from the drums and threw it as far as possible away from the duckboard track called Hunter Street, one to the left and one to the right. Breakages were a nightmare but we managed to cope by floundering through mud when the break was found. We were very often out repairing a breakage when the Engineers were out repairing Hunter Street.

Disturbing incidents at Passchendaele: 1917

Our Observation Post was in a German blockhouse of thick concrete which stood above ground on a small plateau of firm ground. All around were shell holes, yellow with mustard gas and nearly all full of water. The officer on duty slept inside the blockhouse. The telephone and telephonist was at a rough table in the passage entrance and the two other telephonists slept in a three foot high corrugated iron lean-to behind the blockhouse. I recall how we used to crawl on hands and knees into the lean-to to awaken the man who was to take over telephone duty. Two hours on duty and four hours off duty was the regular duty day or night. We dare not show ourselves or display any activity as this would bring on shelling by the Germans.

Canadian soldiers standing on top of a German pillbox. Image courtesy of Australian War Memorial

One night in the darkness some infantry passing by were caught in enemy shellfire and a number were wounded. Shouts of help were heard and my close friend Norman Newton, off duty at the time, went out in the darkness to see if he could be of help. He helped to carry on a stretcher a soldier who had had his arm shot away. It was still in his sleeve but kept dangling down from the stretcher side. A sickening experience for Norman who was much shaken when he returned some hours later.

From our O.P. we looked out over German held territory and the ruined town of Passchendaele. I never actually went into the town as it seemed to be occupied by both sides. So that was our duty for some months, up and down Hunter Street, directing the fire of our guns on the Germans, then back to a spell on the battery telephone, mixed, of course, with the inevitable job of repairing telephone lines broken by shellfire.

Back at the battery eight of us had fixed ourselves up with sleeping quarters in a German pillbox. These were quite different to the blockhouses which stood above ground level and depended on their two foot thick concrete walls for protection. Pillboxes were smaller and sunk into the ground at trench level. The one we occupied was at the end of a trench which opened out in the side of what was a depression in the ground about the size of two tennis courts. The depression was of course half filled with water. We had to go halfway round this depression to reach the battery. We excavated the end of the trench and created a tiny living area about six feet square, with a canvas opening and thick earth sides, corrugated iron roof and a fireplace in one corner, all collected from the surrounding battlefield.

The pillbox itself was about twelve feet by eight feet inside and was entered through a small opening three feet high and the width of a man’s body, on hands and knees of course. We used an old German bayonet to slowly, oh very slowly, scratch out a channel in the concrete to drain the water out. Having done that we put down duckboards (dry wood) to sleep on. Over the many weeks we were in the position with just two guns firing we were as comfortable as we ever had been. Sound sleeping quarters by night and a shielded fire by daylight to keep us warm. We were approaching Christmas 1917 and most days and nights were heavy with frost.

Our comparative comfort was rudely disturbed on several occasions. First our two guns were heavily shelled one day by the Germans. One gun was put out of action and the gun crew had some men killed and most of them wounded. One poor chap had only been with us for two months, a new recruit fresh from England, and he received a shell splinter in his stomach. I saw him being carried away on a stretcher clutching his stomach. He died next day. On another occasion we were shelled and the little, tiny, dug-out in which our telephone was installed was blown sideways. The officer, Lieutenant White, just disappeared. We searched for several hours and eventually found him wandering with loss of memory and shellshock but otherwise uninjured. The telephonist was quite badly wounded. He never came back to France again.

Another incident which hurt me very much at the time was the wounding of my close friend and comrade Norman Newton. I have written earlier that from our pillbox home we went about fifty yards around the rim of the depression to reach the guns and go on duty. I was up at the observation post at the time doing a 24 hour spell of duty. My friend was going on duty at 6 a.m. when halfway round the rim a shell exploded near him and he received a shell splinter through the calf of his leg, fortunately missing the bone.

When I returned from the O.P. he had been taken to an advanced dressing station some miles behind the battery. Although I had done a 24 hour spell of duty without sleep, I asked our sergeant if I could have the day off all duties so that I could go to the dressing station to see Norman. He readily gave his permission and I walked four or five miles before finding Norman in a large marquee with a huge red cross on the top and in one of about twenty beds. He grinned cheerfully when seeing me and said, “I’ve got a Blighty one, Peter.” This meant he was going to England. I sat with him for four or five hours and then set off back to walk the four or five miles to the battery. That was in 1917 and I did not see him again until after the war in 1920 when he came over from Stoke on Trent to my wedding, bringing a lovely tea service as a wedding present.

Another disturbing incident occurred just before Christmas 1917. One of our eight occupants of our pillbox home was going along our well- worn path around the rim from pillbox to battery. When going up the slight rise in the ground, he scraped away some mud while walking and activated a buried German hand bomb. He was badly injured and left us never to return. It could have happened to any one of us as we all traversed the same path.

Just before Christmas it turned frosty and everywhere was white with frost and the ground was hard everywhere. So easy to walk upon compared to the everlasting deep mud. It must be realised that we had dried mud on our outer clothing and halfway up our calf-high boots. Never any parades or inspections, just dirty men doing dirty work – dirty outer clothing and dirty inner clothing. We did manage to wash our underclothes occasionally when the weather was suitable and finally dry them in front of our little fire.

We washed hands and face every morning, also shaved every morning. We fixed up two or three duckboards jutting out into the middle of the little lake and obtained a bucketful of clean water each time for washing. After doing this for a month or so we noticed to our horror a dead German lying in the bottom of the water. Possibly a heavy storm and water movement had washed away the film of earth which had been covering him. Of course we drew our washing water elsewhere afterwards. A dead German was not our business.

When we used to enter our pillbox to sleep at night, when not on duty, there would be probably six of us inside. After crawling in on hands and knees, the last man to enter fixed up a wooden framed chicken wire screen to keep out rats. We learned to do that as a rat got inside one night and caused pandemonium. Even though the screen was up stray rats would come and climb outside the wire trying to get inside. We would poke our knives through the wire to frighten them away.

Once inside and settled for sleep, we lay reading or writing letters home. Remember it was only possible to sit up in the centre of the pillbox as the opposing sides were only one foot high. That is where we placed our heads, our feet met in the middle. Along the back of our heads was a four-inch wide concrete moulding, part of the design of the structure and an admirable place to have a candle for reading or writing purposes.

Canadian soldiers writing letters home near Willerval, France, April 1918

Official Canadian photographer Lt. W. Rider-Rider.

Courtesy of Imperial War Museum, image no. CO 2533.

Now we had an inexhaustible supply of what were known as ‘siege’ candles, hard white wax affairs about the size of a man’s finger. They gave a tiny light and were only for use in ‘siege’ lamps, the only form of light available to us in the dark hours. They were used on the guns at night time.

Well there were seven of us, four one side and three the other, feet to feet reading or writing. Suddenly there was a terrific explosion outside and our pillbox home rocked like a small boat on a rough sea. Every one of the dozen or so candles went out with the air shock and we were left in darkness wondering what had happened. We scrambled out one by one on hands and knees and found a German shell had actually hit our pillbox, breaking off a piece of concrete at one corner about the size of the body of a wheelbarrow. The pillbox undoubtedly saved our lives. It was a frightening experience.

Passchendaele: Christmas 1917 – Spring 1918

It was just before Christmas 1917 and we were told we should still be in the same position into the New Year. That meant that we signallers had to maintain the pillbox living quarters into 1918. We were also told we would have to do our own cooking on Christmas Day. No reason was given for this once and for all decision. We would be given a day’s ration in raw uncooked form. So we set about building an oven in the side of the trench outside the pillbox. We searched for and found an empty five gallon oil drum, cut off the top with an old German bayonet and a piece of stone as a hammer. We thoroughly cleaned it with boiling water. That was our oven. We laid it sideways on bricks, two a side, a hole in the earth at the back and there was our cooking oven. The fire between the bricks was fed by old pieces of timber lying all around us.

On Christmas morning our rations arrived: a leg of pork, green vegetables and potatoes. We roasted the pork in our oven and cooked the vegetables over a second fire. We had plenty of Australian butter and used some to cook the pork. The meal was delicious. We had not tasted roast meat since coming out to France years earlier.

We had a rum ration every evening when our sergeant poured out a measured tot into our mess tin. We were supposed to drink it in front of him but for weeks I had been storing mine up until I had a wine bottle full by the time Christmas Day came. The seven of us drank it all on Christmas Day 1917. I had never been a drinker and was not very keen on it but drinkers were always hovering around when the rum issue was being given. They offered a tin of jam in exchange for a tot of rum.

After Christmas 1917 the routine continued: spells up at our observation post in the ex-German concrete blockhouse, up Hunter Street and down Hunter Street, repairing telephone lines between battery and O.P., also repairing and maintaining telephone lines between the split up sections of the battery. At this period our battery of six guns was split into three sections of two guns each. It was very difficult to maintain these different routes.

Then one night in February 1918 our horses came up to move our two guns to a new position. All night long in the dark they struggled, slipping down, getting them up and trying again. The mud was such clinging, sticky stuff the horses could not move the guns at all. Shortly before dawn the effort was called off and the horses were led away.

A team of eight horses pulling a 4.5 inch howitzer through mud near Courcelette, March 1917

Official war photographer Lt. John Warwick Brooke. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, image Q5011

Nothing happened for a couple of days and then one night we were astounded to see one of the new tanks come up to pull our guns out of the mud morass. It was our first sight of tanks and it amazed us to see them dragging the guns with apparent ease through the mud.

And so we left Passchendaele and our pillbox home with all its memories. Of the area itself I can only add that it was inhuman for men to be asked to live, work and fight in such conditions. I repeat again and again they were appalling.