Radcliffe on Trent War Memorial

Radcliffe on Trent War Memorial 1921

Radcliffe on Trent War Memorial is an enduring symbol of the losses suffered by the village in the First World War. When the war was over Radcliffe on Trent, like thousands of towns and villages across the UK, tried to make sense of the tragic events of the previous years and move forward. A memorial to those who died was a means of bringing the community together as well as an act of remembrance for those who would never return to the village.

There were no national guidelines for the form or design of local war memorials. Each town and village employed its own method. A public meeting was held in Radcliffe on 2nd May 1919 to consider various possibilities. Suggestions included a village hall, a memorial cross, a lych gate and an endowment fund for parents who had lost sons in the war. A year later plans were underway for building a memorial cross. Minutes of the Easter Vestry, held on April 7th 1920, record the committee approving ‘the erection of a soldier’s cross at the east end of the (St Mary’s) churchyard by the parishioners in memory of the gallant men of Radcliffe on Trent who fell in the great war 1914─1918’. A faculty (licence to carry out work on Church of England property) was granted on 31st July 1920.

The memorial’s prominent position and iconography is a visible reminder of how Radcliffe residents wanted the dead to be remembered. Overlooking the main road into the village, it is built in the form of a Celtic cross featuring a nimbus or ring. A bronze figure of St George, symbolising heroism and national identity, is set in the column. The primary inscription on the east face, below St George, reads ‘In memory of the gallant men of Radcliffe on Trent who fell in the Great War A.D. 1914–1919’. The biblical phrase ‘Their name liveth for evermore’, chosen by Kipling for war memorials at home and abroad, is inscribed on the plinth, linking Radcliffe men to all who lost their lives. Fifty-two names of those killed abroad are inscribed on the north and south faces of the plinth and nine names of those who died of illness on the west face.

How Radcliffe War Memorial names were chosen

It has been difficult to establish how the sixty-one names on Radcliffe’s memorial were chosen. We have been unable to find, for instance, Parish Council or any public meeting minutes relating to the matter. However, a pattern has emerged through analysing our biographies of men on the memorial. While only twenty-nine of the sixty-one commemorated were born in Radcliffe, the majority (fifty-two men) had family residing in the village after the war. Six of the nine men without local family ties had lived and worked at the Notts County Asylum. One man had been a teacher at the village school, one was the son of the deputy clerk in Nottingham and one, an orphan, had been billeted in the village. The memorial does not record all previous residents who lost their lives because of the war; it prioritises those connected to people who were still living in the village around 1920.

Minutes taken at St Mary’s Church bell-ringers annual meeting, 1st January 1919, reveal an early attempt to list the war dead. The bell ringers noted names of forty-one men, who subsequently appeared on the memorial, in order to ring a half muffled peal of bells in their honour. It is not known if this list was discussed at the 1919 public meeting; it is plausible that it formed the basis for decisions regarding men’s eventual inclusion. By the time of the unveiling, another eighteen names had been added and two names were inscribed later.

The names on the Radcliffe War Memorial are not an exact list of Radcliffe’s war dead. Our research has uncovered a further twenty-two local men and one woman who died as a consequence of their war service but who are not included on Radcliffe’s memorial. Several of them were born in Radcliffe, attended the school or worked in the village. The main reason for their exclusion appears to be weak family links to the village after the war. Seven of them are buried in Radcliffe cemetery and most are commemorated on memorials elsewhere.

Unveiling the Memorial 1921

Radcliffe on Trent War Memorial was unveiled on Sunday afternoon, 27th March 1921, by local resident Lt. Col. Charles Birkin, who had commanded the 1st/7th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters from 1914–1915. The ceremony began with a procession of around 250 Radcliffe ex-servicemen, fronted by the local brass band playing the Dead March from Handel’s Saul. The men formed up in St Mary’s churchyard where a great many villagers were present.Buglers from the 1/7th Sherwood Foresters, also known as the Robin Hood Rifles, sounded the Last Post and Reveille. A service was conducted by local minister, the Rev. Cecil Smith.

Addressing the crowd, Lt. Col. Birkin then paid tribute to the men who died. He said: “Radcliffe on Trent lost too many of the flower of its youth – men who could ill be spared, and could not be replaced – and the sympathy of all went out to the relatives. It must be a source of pride to them that the names of their dear ones would be inscribed for ever on the roll of honour of the village.It was my good fortune, whilst serving in France, to see the devotion to duty and heroism of men such as those whose names are on this memorial, and I can say it left an impression on my mind that can never be effaced; and made me proud to be a member of the British nation and able to call such men my fellow countrymen”.

The cross was unveiled as he spoke, revealing the bowed headed figure of St. George and the inscribed men’s names. The Rev. Hales, rector of Cotgrave, dedicated the cross. He told the crowd that they must see that the men’s sacrifices were not in vain and that their loved ones were not forgotten. He commented that the war was won by unity and that ‘whenever discords arose people should visit the memorial, think, and strive for unity at home’. Relatives laid wreaths on the memorial at the end of the service, beginning the tradition that continues today.

Click here for a full list of those on the memorial with links to their biographies

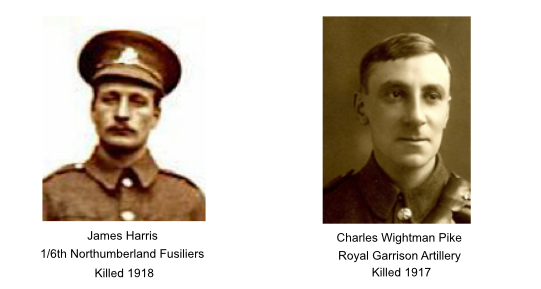

The men on Radcliffe War Memorial

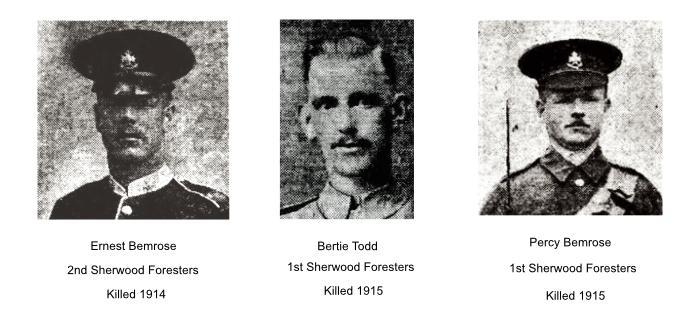

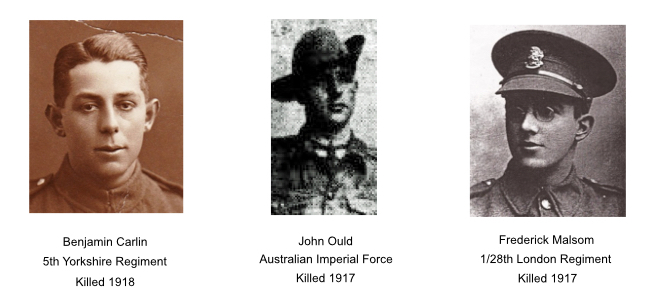

The sixty-one commemorated men reflect the composition of the British Expeditionary Force in that they comprise a small number of regular soldiers, reservists and territorials and a larger number of volunteers and conscripts. Forty four were infantry and eight were artillery men. The remaining nine fatalities came from the Yeomanry (2), Royal Flying Corps/RAF (2) Royal Army Service Corps (2) Guards (1) Machine Gun Corps (1) and Royal Engineers (1). The men came from different social backgrounds. Most had manual occupations before the war such as gardeners, builders’ labourers, electricians and so on. Some had occupations in the legal and teaching professions.

Regular army and reservists

Thirteen of those commemorated were regular soldiers or reservists. Such men were the first to be sent to the front and the most exposed to continual danger.

Territorials

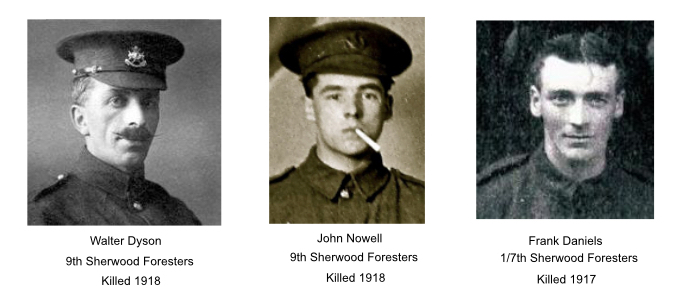

Territorial Forces were created in 1908 as a part-time form of soldiering. Most infantry regiments formed territorial units (for example, the 1/7th Sherwood Foresters). Men who had joined the Territorials before the outbreak of war were under the same mobilisation obligations as reservists. Men on the memorial known to have been in the Territorials are Frank Daniels, John Martin, John Nowell and John Stafford.

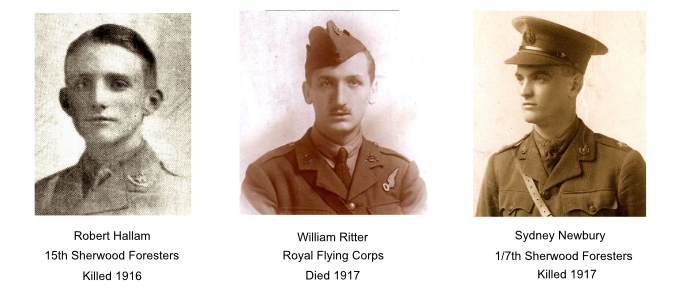

Officers

Six of the seven officers commemorated entered the war as volunteers and were then commissioned: Five lived in large houses in the village (three lived next door to each other) and had fathers with professional occupations. The officers’ names are Robert Blatherwick (2nd Lieutenant, West Yorkshire Regiment), Percy Cox (2nd Lieutenant, Northumberland Fusiliers), Robert Hallam (2nd Lieutenant, Sherwood Foresters), Sydney Newbury (2nd Lieutenant, Sherwood Foresters), John Richards (Lieutenant, Royal Naval Division), William Ritter (Lieutenant, Royal Flying Corps). Robert Blatherwick and Robert Hallam were in action for no more than seven weeks; the service of the other deceased Radcliffe officers lasted around two years. A seventh officer commemorated, Ernest Eastwood, rose through the ranks and was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1917 after 21 years of service. He died of cancer in 1918.

Volunteers and conscripts

Men who enlisted before conscription came into force in 1916 were deemed to be volunteers. The Nottingham Evening Post reported on 16th October 1915 that Radcliffe on Trent had produced a record number of volunteers:

Up to the present Radcliffe has supplied 169 men to His Majesty’s Forces and in addition 27 warders have gone from the County Asylum – a total of 196. Of these three have been killed, two are missing and several are and have been wounded. Four sons have gone out from one home, three out of another and in 22 homes two sons have gone from each. In three cases fathers and sons are serving and from 30 homes the only son has volunteered.

Single men between the ages of eighteen and forty-one were obliged to enlist from 2nd March 1916. A further conscription act in May 1916 extended liability to married men. Thirty-seven of those on the memorial were either volunteers or conscripts. The number in each category is not known due to lack of information.

Sherwood Foresters

Men from the same locality often joined their county regiment and went off to fight together. But the ‘Old Pals’ pattern didn’t happen in Radcliffe. The county regiment for Nottinghamshire was The Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire & Derbyshire Regiment). It attracted high numbers of local recruits but so did the Royal Artillery. Although many who enlisted in the Sherwood Foresters stayed with them, the regiment also acted as a filter; some passed through quickly and joined other military units on arrival in France. Nevertheless, the Sherwood Foresters is the dominant regiment on the memorial, accounting for a third (twenty-two) of the names.

Length of time in action

The majority of the men on the memorial had only spent a short time in combat before losing their lives. Almost half were killed in the first few months after entering one of the theatres of war – thirteen were killed in less than six months. Only two survived more than three years: Bertie Bemrose and Horace Beet, both regular soldiers.

Age of those on Memorial

Half the men (thirty-one) on the memorial were in their twenties. Fifteen were under twenty-one and fifteen were over thirty. The average age at death was twenty-six. Robert Hallam at seventeen was the youngest to die, falling at the Somme. Benjamin Carlin and Samuel Parkes were eighteen when they were killed in action. Sidney Bell, aged forty-six, was the oldest to die and Walter Dyson, aged forty, the oldest to be killed in action; he lost his life on November 4th 1918.

Married men on Memorial

Married Radcliffe servicemen were more likely to survive than single men. During the war 165 married Radcliffe men and 235 single Radcliffe men were on active service. 88% of Radcliffe husbands returned to their wives and children but only 81% of single men came back. There are sixteen married men named on the war memorial compared with forty-five single men. Sixteen Radcliffe women, most of whom had children, became war widows.

Impact on families – read more

Pattern of deaths

Deaths increased as the war continued. Eight Radcliffe servicemen died in 1914 and 1915. Conscription was introduced in 1916 and fifty-three Radcliffe men named on the memorial died from that year onwards. 1918 was the worst year when there were eighteen Radcliffe deaths. The Battle of the Somme was the worst conflict involving thirteen Radcliffe fatalities, three of whom were killed on the first day.

Deaths abroad

Forty-eight of those commemorated died abroad. Thirty-eight of them were killed in action and ten died of wounds or illnesses, including influenza, at casualty clearing stations or military hospitals. Half of the forty-eight who died abroad have individually marked graves in Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) cemeteries. The bodies of the other twenty-four men were not recovered; they are remembered abroad on CWGC memorials, such as Thiepval Memorial to the Missing.

Click here to find out more about the conflicts in which the men died.

Deaths in the UK

Thirteen men died from illnesses at home between 1915 and 1923. Nine are buried in Radcliffe cemetery.

Click here to read about WWI graves in Radcliffe cemetery

Four are buried elsewhere: Sidney Bell (heart disease, buried New Zealand), Thomas Buggins (tuberculosis, buried Bingham), Arthur Clarke (heart disease, buried County Durham) and Leonard Rushmore (gas poisoning, buried Nottingham).

The memorial distinguishes those killed in action or dying of wounds from those who died from illness contracted while on active service by listing the two groups separately on the plinth. However, there are errors in this separation with six men who died of illnesses not assigned to that category. (See the biographies of H. Beet, S. Bell, T. Buggins, G. Berridge, J. Martin and L. Rushmore for details of their deaths).

Impact of WWI on Radcliffe servicemen’s health

The majority of Radcliffe on Trent servicemen returned; we have recorded around 320 who came back and were still alive five years after the end of the war and eighty-five who died between 1914 and 1923, sixty-one of whom are on the memorial.

The men’s war experiences were variable, as was their length of service. A great many men were reported sick or wounded while serving. Some were reported as being dangerously ill and narrowly escaped death. The Radcliffe on Trent biographies reveal an overall deleterious effect of the war on men’s health and shorter life spans than generally experienced today. Many ex-servicemen who survived the war died in their fifties and sixties.

War-related deaths continued long after the Radcliffe on Trent memorial was erected. Seven ex-servicemen from the village died between 1924 and 1929. A further nineteen died in the 1930s. By 1939 just over a quarter of all Radcliffe WW1 servicemen (109 men) were no longer alive. The pattern of poor post-war health found among ex-servicemen in Radcliffe was replicated nationally: tuberculosis was a lethal killer at the time. The long term consequences of war cut short the lives of thousands of men across the U.K. and because of the time lapse since the end of WWI they were not officially commemorated.

Radcliffe War Memorial today

Radcliffe on Trent War Memorial is still a place for commemoration. People often leave wreaths on the memorial base after funerals. Every November Radcliffe residents congregate at the memorial to commemorate those who died as a result of the Great War, alongside those who lost their lives in the Second World War and more recent conflicts. A special ceremony took place at the war memorial on November 11th 2018 to commemorate the centenary of the Armistice. Local dignitaries, community groups and organisations, including Radcliffe on Trent WWI Group, paraded through the village before laying wreaths at the memorial’s base. There was a huge crowd in attendance, just as there was when the memorial was unveiled in 1921.

Radcliffe on Trent Memorial, November 11th 2018

Click here to read more about the Armistice centenary in Radcliffe

Rosemary Collins, March 2019