Belgian Refugees in Radcliffe on Trent and Nottingham

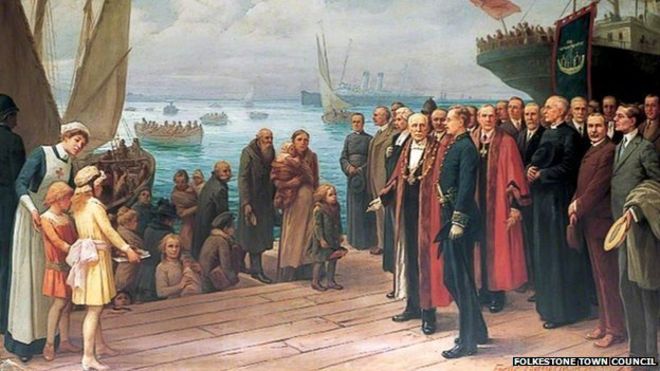

A 1915 painting by Fredo Franzoni shows Belgian refugees landing in Folkestone. It hangs in Folkstone town hall

The plight of refugees is one of the biggest challenges facing the world today. There are currently over a million in Europe, many of whom have fled from war torn Syria, Afghanistan and the Sudan. The UN Refugee Agency reported in October 2017 that 144,656 refugees had risked their lives reaching Europe by sea in 2017 and 2,784 had drowned. Children are particularly vulnerable. In February 2017 it was estimated that there were 95,000 unaccompanied minors waiting in camps in Europe to be transferred to a safe haven; the majority of whom were young teenage males.

Asylum seeking refugees are not a new European problem. The story of displaced people across Europe both during and after WWII is fairly well known but the refugee crisis of WWI is more hidden. A hundred years ago the First World War created thousands of refugees but, in contrast to today, the British government’s response to displaced people was welcoming. As Ian Hislop pointed out in his June 2017 TV programme Who Should We Let In?, the Victorian approach to refugees was based on the idea that Britain was the asylum of nations. This attitude persisted in the early twentieth century and keeping the door open for everyone was seen as an act of moral leadership. When Germany invaded Belgium in 1914, there was a mass exodus of its citizens; around 1.5 million fled the country and another half a million were internally displaced. Britain, bound under the Treaty of London (1839) to protect Belgian neutrality, declared war on Germany and soon became home to 250,000 Belgian refugees. Unlike today, when refugee journeys across the sea to unspecified European destinations are hazardous, boats from Belgium landed their passengers safely on British shores. On October 14th alone, 16,000 refugees arrived in Folkestone (BBC News Magazine, 15 September 2014).

Belgian Refugees at Victoria Station 1914 IWM (Q 53305)

Belgian refugees in Nottingham

The sudden influx of Belgians in Britain brought the consequences of war home to people all over the country. The War Refugees Committee coordinated relief work and set up 2,500 local committees to welcome and house the high numbers. As the photograph above shows, a great many refugees arrived as family units; the twenty-first century problem of unaccompanied minors was uncommon. Initially, people responded positively to the refugees’ plight; housing and helping them became a way of contributing to the war effort. In 1914 the newspapers were full of articles about the refugees; as the war continued, media interest waned.

Nottingham was well prepared to accommodate Belgian refugees, who started arriving by train from September 1914 onwards. By the middle of October the local relief fund appeal had raised just over £3,500. On October 22nd 1914 the Nottingham Evening Post reported the arrival of sixty-three Belgian refugees. They were transported from the station to the central depot at the Eagle works, Carlton Road, where they received temporary hospitality before being dispersed to furnished homes around the city: ‘They represented the poorest class and were apparently greatly distressed. Coming from various parts of Belgium, some related terrible experiences and an old woman of about three score years and ten was a pathetic figure.’ Another contingent of around 200 arrived in November 1914. Fifty nine ‘families of the middle class’ remained in the city while their compatriots departed for Leeds and Bradford after being fed at Nottingham station. By 1916, 938 refugees had arrived in Nottingham.

Considerable efforts were made to accommodate the refugees and meet their needs. At the end of October 1914, Nottingham University offered free admission to any lectures or classes in addition to an English class held every Thursday afternoon. Several property owners offered Belgians empty houses in the city rent-free; they were then furnished by the refugee committee. In December 1914 arrangements were made for Belgian children to attend two catholic schools in the city. In 1916 a club was opened on Derby Road near the Roman Catholic Cathedral as a place for refugees to meet. It had a small library, provision for French and English newspapers and other facilities. In 1917 a Belgian school opened on Derby Road, allowing children to be taught in their own language and in line with their cultural requirements.

Belgian refugees in Radcliffe on Trent

Women from Radcliffe on Trent were involved in the Nottingham fund raising scheme for the Belgian refugees. Claire Birkin from Lamcote House was chair of the Nottingham committee and a leading fund raiser for the Belgian Red Cross:. She organised fund raising events throughout the war. On October 16th 1915, for instance, she brought together a thousand helpers, including female Belgian refugees and women from Radcliffe, to sell flags in the city. They raised £1000. By 1917 the people of Nottinghamshire had donated £14,000 to the Belgian Red Cross. The Nottingham Evening Post commented on June 15th: Admiration for the bravery and self-sacrifice of the Belgians should make the appeal of the Belgian Red Cross, which is made tomorrow in the city and county, a popular one.

A few refugees came to live in Radcliffe on Trent. However, like the bigger story of Belgian refugees in Britain, their stay in the village is partially hidden. It is not known how many came, how the community responded and what assistance they were offered. Who were they?

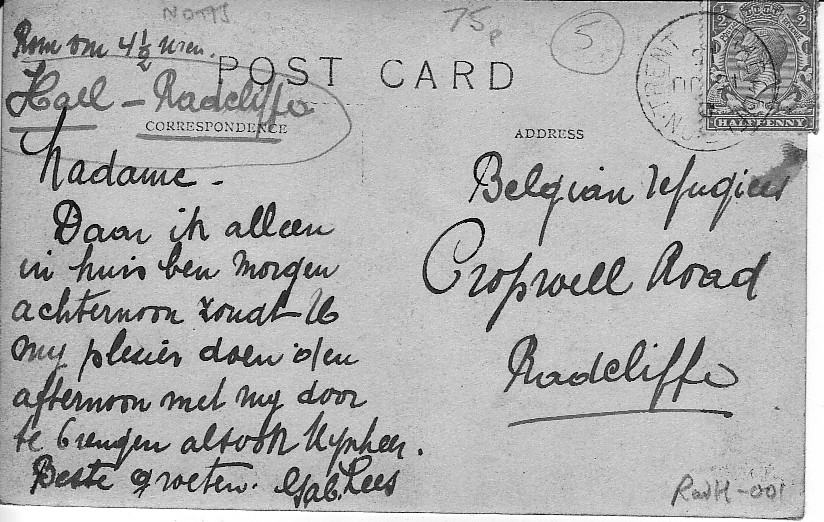

Tenuous clues come from a postcard, gravestone and the correspondence of Lydia Evaert-Faveers, a Belgian befriended by a Radcliffe family. The Radcliffe WWI group is investigating these clues about displaced Belgians to try and establish how these people fit into the wider narrative of the greatest influx of refugees in British history. The postcard below was found in the archives of the local history society. It is addressed to ‘Belgian refugees’, written in old Flemish and sent from Radcliffe Hall, a private home which became a convalescent hospital for officers; the writer may have been a lodger, nurse, patient or servant. The address, Cropwell Road, is no more than ten minutes’ walk from the Hall. The message reads: Madame, as I’m alone at home tomorrow afternoon, it would be a pleasure if you could pass the afternoon with me, also Mister. Best regards, Gab. Lees.

While the postcard suggests there were a few refugees settling into living in Radcliffe, a sadder story concerns the Belgian who died locally in November 1915, at the age of fifty-three. The gravestone of Camiel van den Broeck, 1862-1915, born in Ghent, stands in Radcliffe cemetery. His epitaph reads ‘Far from his home and the land of his birth’. Camiel was probably among a small group of refugees who arrived in Mansfield in December 1914. At some point he was admitted to Notts County Asylum, Saxondale, where he died on November 27th 1915. The asylum had begun taking in a few military patients suffering from war trauma; it is possible that he was admitted as a result of his experiences in Belgium. Most patients who died at the asylum were buried in unmarked graves in Radcliffe cemetery; Camiel van den Broek’s headstone stands among those unmarked graves. His grave is shared with Samuel Porter, who died in Bingham workhouse in 1910, and Frank Holmes, place of death currently unknown. He left a widow, Brunetta van den Broek, who lived at 11 Harcourt Street, Mansfield.

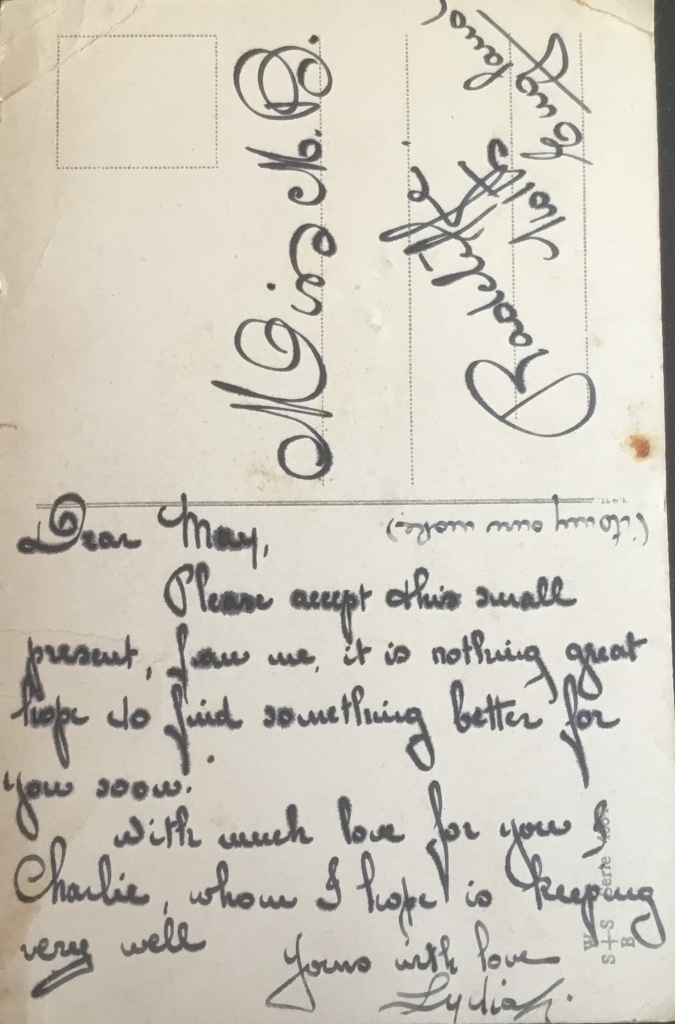

In 2017 the Radcliffe WWI Group was contacted by descendants of the Bemrose family. The Bemroses had lived in Radcliffe on Trent for generations, including during the Great War. The descendants had in their possession a photograph, postcards and a letter from a Belgian refugee, Lydia Evaert Faveers who spent time in the village during WWI. The correspondence was addressed to May Bemrose, the daughter of Walter Bemrose, the Radcliffe village sexton and his wife Elizabeth. May had three brothers, Harry, William and Tommy and three sisters, Hannah, Ethel and Cissie. The family lived in Richmond Terrace in a house with five rooms. In 1911, when she was fourteen, she was working as a cigar maker. Some of her older brothers and sisters had moved out of the family home and she was now living with her parents and siblings Cissie, Ethel and Tom. During the war May’s brothers, William and Tom, served in the Royal Field Artillery and her sister Cissie, now married to Horace Wesson, worked as a Red Cross clerical officer at Notts.County War Hospital.

Lydia Everaert-Faveers (front left) and family – the photograph was taken in Nottingham

The Bemrose descendants assumed that Lydia had lived with May’s family during the war. However, given the size of the house and the fact that refugee families were usually housed together, it is as likely that she lived elsewhere with her parents and brother but had developed a friendship with May. Many Belgians found employment during their stay in the U.K; typical industries employing them across the country were munitions, textiles and agriculture. It is possible that Lydia and May met in the workplace. The family’s address and business in Belgium was ‘Eug. Everaert-Faveers, Plombier, Rue des Dunes, 19-11, Heyst’ (now part of the coastal area of Knocke-Heist) where they returned after the war. Their shop in Heyst, called Albion Sanitaires, sold bathroom appliances. Lydia wrote to May and her future husband Charlie from this address after returning to Belgium and enclosed the above photograph. She wrote:

Dear May and Charlie,

Ever so many thanks for your nice box of chocs, which came to hand this morning, I was surprised to get a parcel in my own name and my surprise still grew bigger when I opened it! ‘Oh you ducks’! How kind of you to remember me. I was quite happy to see that although we are separated from each other for miles and miles, our acquaintance is growing no weaker. I am sure that if I did not get news from England now and then that that I feel somehow that life is not worth living.

Lydia’s letter suggests that her time spent in England was a positive experience, leading to new friendships and interests. She continued:

I have been longing for five years to come back to our country and now while there is plenty of work and much money to be earned, we could have been so happy amongst ourselves only as fate would have it… . Still we have to make the best of things. I have plenty of work. I do the cooking, look after the shop, do the office work, have to see to house duties …

It is not known what difficulties Lydia and her family faced on returning to Belgium but the sentence ‘as fate would have it’ suggests that something untoward had happened. Her letter goes on to ask if there was anything fresh in Radcliffe or in Nottingham, any marriages, births or deaths in which I am interested suggesting she still felt ties to Nottinghamshire. The letter concludes:

I don’t think I have much to tell you May, only I hope to tell you more next time. With many thanks and much love for you both. I will close,

Yours sincerely, Lydia

P.S. Please accept this little photo from myself as a keepsake. Write me soon will you May. I am looking out for your letters.

Lydia sent further postcards to May including the one below. There may have been additional correspondence that has been lost in the course of the last hundred years.

Living in Britain as a Belgian refugee from 1914–19

As the war continued, less attention was paid to the plight of Belgians exiled in Britain than at the time of their arrival. Friction emerged in places between the two communities around such things as incidents in the workplace and petty crime. The situation in Nottingham seems to have remained positive; there are several references in the Nottingham Evening Post concerning Belgian integration. In 1915, for example, Mademoiselle Sidonie Rogaerts wrote to the paper expressing her gratitude for the garden party arranged by the Belgian Refugees Committee in honour of the 85th anniversary of Belgian independence. She noted that, We all felt a real satisfaction and we lived for a few hours in remembrance of better days passed before in our lovely little Belgium. We felt in those moments more than we could tell of thankfulness and friendship, because we are no more strangers in a foreign country and everybody has found friends, and even more than friends.

From the Nottingham Evening Post September 1914

From the Nottingham Evening Post September 1914

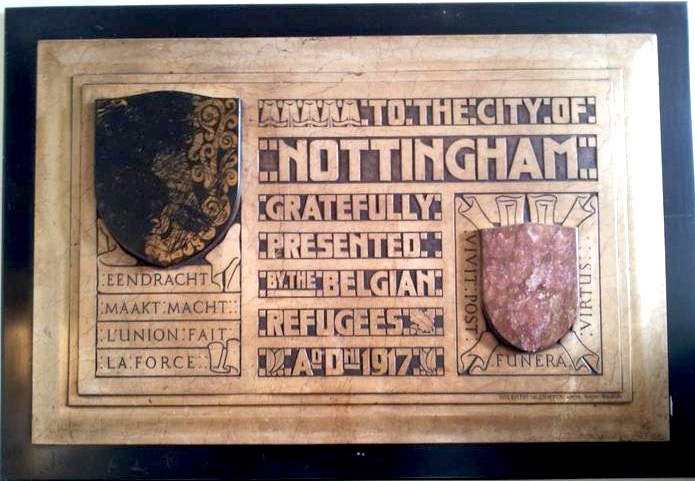

In January 1917 the members of the Nottingham Belgian Club, known as the ‘Albert-Elisabeth’ decided to show their appreciation by donating a tablet to Nottingham Guildhall inscribed ‘Gratefully presented by the refugees, A.D. 1917′. The memorial tablet was based on a design by Belgian architect Valentin Vaerwyck, a refugee in Nottinghamshire. Later that year the mayor of Nottingham, Mr Pendleton, opened an exhibition and sale of lace made by female Belgian refugees. The exhibition took place in Nottingham’s prestigious Albert Hall, the sale covered the cost of materials and the remaining profit went to war charities.

After the War: return to Belgium

When the war ended, the government encouraged refugees to return to Belgium and often paid their passage home. Restrictions were placed on Belgians continuing in employment; cuts in wages were an incentive to leave jobs that were now required by returning servicemen. On February 12th, 1919, Nottingham said goodbye to 230 Belgian refugees at the train station. Mlle. Sidonie Rogaerts was in charge of the party and the Midland Railway Company laid on a special train. The refugee committee gave each person sandwiches for the journey. Mr Pendleton and the Sheriff of Nottingham both gave a speech on the platform. Mr Pendleton said I hope the hospitality we have showed you in times of trouble will form the basis of a lasting friendship between the two peoples. I can only express the hope that your future will be a bright and happy one and that your country will become greater still and enjoy the blessings of a durable peace. The Nottingham Evening Post report continues: Cheers were raised for Belgium and for Nottingham as the train steamed out of the platform on the way to Hull. From this point the travellers will embark for Antwerp which is the dispersal station and at which point the Belgian Government will assume responsibility. Lydia’s letter, with its postage showing the address of the family business, suggests that some of them returned to their old homes and occupations to pick up the threads of lives interrupted by the war. By June 1919 only a handful of refugees remained in Nottinghamshire.

The Belgian Government showed its appreciation for efforts made on behalf of the refugees when the war was over. On January 8th 1920, Alderman J.E. Pendleton, now deputy mayor, was made an officer of the Order of Leopold – a high distinction. He received a star made of gold, blue and white enamel and a complimentary letter from the Belgian Minister for Foreign Affairs. Alderman Pendleton was chair of the Belgian Relief Committee and ‘rendered other services on behalf of the Belgian cause‘. He was one of only six people to receive the decoration in the U.K. On June 12th 1920, Mr Pare, chair of the West Bridgford refugee committee, was presented with the ‘Palm of the Order of the Crown’ forwarded by the King of Belgium. When making the presentation, the Chairman of West Bridgford Council commented on the generous hospitality shown by the people of the district to the unfortunate Belgians. Claire Birkin from Radcliffe on Trent was awarded the Médaille de la Reine Élisabeth (1914-1918) by the Belgian government. The medal was created by royal decree on 15th September 1915 and was an acknowledgement for those who had cared for suffering victims of war for at least a year before 10th September 1919. Photographs of Claire Birkin in the 1920s show her wearing her medals on civic occasions. She was chair of the local ladies branch of the Conservative Party at the time.

It is known that some Belgian refugees were domiciled in Nottinghamshire villages near Radcliffe on Trent. The war memorial in Gunthorpe, for instance, was designed and presented to the village by architect Valentin Vaerwyck who had lived there during the war as a refugee (source: www.southwellchurches.nottingham.ac.uk). He also designed the memorial tablet in Nottingham Guildhall.

By 1921, 90% of the Belgian refugees had left the country. The extent to which Belgians kept in touch with their British hosts is not known; the letter from Lydia Everaert-Faveers is an example of how some people wanted to maintain contact across the channel after the war was over. The larger story of Belgians in Britain was neglected for decades and did not attract much academic interest until the late 1990s. Research groups are now assembling the facts and linking local, regional and national projects. Among them are the Institute of Social History at the University of Ghent and the People’s History Museum, Manchester. They are looking for stories about the Belgians who came to Britain and the people who helped and housed them. ‘Collection Days’ aiming to bring together people’s recollections and documented materials were held in November 2016 in both Belgium and in the U.K.

Read more at www.belgianrefugees.blogspot.co.uk

Author: Rosemary Collins

November 2017